Pi Day is here! We bet that you know that famous constant to a few decimal points, and you could probably explain what it really means: the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. But what about the constant e? Sure, you might know it is a transcendental number around 2.72 or so. You probably know it is the base used for natural logarithms. But what does it mean?

The poor number probably needed a better agent. After all, pi is a fun name, easy to remember, with a distinctive Greek letter and lots of pun potential. On the other hand, e is just a letter. Sometimes it is known as Euler’s number, but Leonhard Euler was so prolific that there is also Euler’s constant and a set of Euler numbers, none of which are the same thing. Sometimes, you hear it called Napier’s constant, and it is known that Jacob Bernoulli discovered the number, too. So, even the history of this number is confusing.

But back to math, the number e is the base rate of growth for any continually growing process. That didn’t help? Well, consider that many things grow or decay through growth. For example, a bacteria culture might double every 72 hours. Or a radioactive sample might decay a certain amount per century.

Classic

The classic example is compound interest. Suppose you have $100, and you put it in the bank for a 10% per year return (please tell us where we can find that, by the way). So at the end of the year, we have $110, right? But what if you compound it every six months?

To figure that out, you look at the $100 after six months. The annual interest on the money is still $10, but we are only at 6 months, so prorated, that $5. Therefore, after six months, we have $105. At the end of the year, we look at the 10% of $105 ($10.50). That’s still for a year, so we need to halve it ($5.25) and add it in ($105+105.25=110.25). So, compounding every six months means we get an extra quarter compared to simple interest.

What if it was compounded monthly? Now, we divide our interest by 12, but we have a little more money every month. After the first month, we have $100.83 ($100.00 + 10/12). The second month’s net is $101.67. By the end of the year, you have $110.47. Not quite twice as much extra as you had before.

So what if you could compound weekly? Or daily? Or hourly? Generally, you’ll get more, at least up to a point. Eventually, the interest will be split up so much that it will balance the increase and, at that point, you won’t make any more. There is an upper limit to how much money we can have at the end of the year at 10%, no matter how often you compound the interest.

So Where’s e?

Assume you could get a 100% return on your money (definitely let us know how to do that). That means if you go for a year, that’s a return of 2 — you double your money. But if you split the year in half and compound, you get 2.25 times the original amount. You can try a few more splits, and you’ll find the equation for growth is (1+1/n)n. That is, if you only compute it once (n=1), you get double (1+1). If you compute interest twice, you get 2.25 (that is, (1+1/2)2).

If you set n to 1,000, the return will be 2.7169. That’s even better than 2.25. So 100,000 should be wildly better, right? Not so much. At 100,000 you get a 2.71814 return. At 10,000,000 the rate is 2.71828 (or so).

Look at those numbers. Going from 1,000 to 10,000,000 only increases yield by about 0.001. If you know calculus, you might know how to take the limit of the growth equation. If not, you can still see it is going to top off at around 2.718. Those are the first digits of e.

Of course, e is like pi — transcendental — so you can’t ever get all the digits. You just keep getting closer and closer to the actual value. But 2.718 is pretty close for practical purposes.

Scaling

We can scale e to whatever problem we have at hand. We just have to be mindful of the starting amount, the rate, and what a time period means. For example, to work with our 10% rate (instead of 100%) we have to consider the rate e0.10 or about 1.105. Then, to scale for amounts, we have to multiply by the rate. So remember our $100 at 10% example? Our maximum return is 100 x 1.105 = 110.50. Why did we only get $110.47? Because we compounded 12 times. The $110.50 result is the maximum.

More Years

You can also multiply the rate by the number of periods. So if we left the money in for five years: 100 x e(0.10 x 5). If you think about it, then, making 50% for one year has the same maximum as making 10% for 5 years (or 25% for 2 years).

Negative Growth?

Suppose you have 120 grams of some radioactive material that decays at a rate of 50% per year. How much will be left after three years? Simplistically, it seems like the answer is that it will be depleted after two years. But that’s not true.

Just as compounding adds more money, a decay rate removes some of the radioactive material, meaning the absolute decay rate gets slower and slower with time because it is a percentage of the radioactive material’s mass.

Just for the sake of an example, suppose at some imaginary small period, the sample is at 100 grams and, thus, the decay rate is 50 grams/year. Later, the sample is at 80 grams. The decay rate is 40 grams/year, so it will take longer to go from 80 to 60 than it did to go from 100 to 80.

In this case, the rate is negative, so the formula will be 120 x e(-0.5 x 3). That means you will have about 26.8 grams of radioactive material left in three years.

Modeling

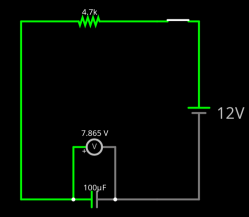

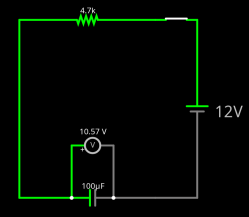

Consider the classic equation for an RC circuit: Vc=Vs(1-e(-t/(RC))). Here, Vc is the capacitor voltage, Vs is the supply voltage, t is in seconds, and RC is the product of the resistance in ohms and the capacitance in farads.

What can we infer from this? Well, you could also write this as: Vc=Vs-Vs x e(-t/(RC)). Looking at our earlier model for money, it is plain that Vs is the voltage we start with, t is the time, and rate is -1/RC (time can’t be negative, after all). That makes sense because RC is the time constant in seconds, so 1/RC is the rate per second. The formula tells us how much voltage is charged in the capacitor, and subtracting that from Vs gives us the voltage drop across the capacitor.

Think about this circuit:

At t=0, we have Vs(1-e0), which is 0. At t=0.5, the voltage should be about 7.86V; at t=1, it should be up to 10.57V. As you can see, the simulation matches the math well enough.

Discharging is nearly the same: Vc=V0 x e(-t/(RC)). Obviously, V0 is the voltage you started with and, again -1/RC is the rate.

So Now You Know!

There’s a common rule of thumb that after a time period (RC) a capacitor will charge to about 63% or discharge to about 37%. Now that you know the math, you can see that e-1=0.37 and 1-e-1=0.63. If you want to do the actual math, you can always set up a spreadsheet.

Anything that grows or shrinks exponentially is a candidate for using an equation involving e. That’s why it is a common base for logarithms. Of course, most slide rules use logarithms, but not all of them do.

(Title image showing e living in pi’s shadow adapted from “Pi” by [Taso Katsionis] via Unsplash.)

This articles is written by : Fady Askharoun Samy Askharoun

All Rights Reserved to Amznusa www.amznusa.com

Why Amznusa?

AMZNUSA is a dynamic website that focuses on three primary categories: Technology, e-commerce and cryptocurrency news. It provides users with the latest updates and insights into online retail trends and the rapidly evolving world of digital currencies, helping visitors stay informed about both markets.